Like many other American cities, New York City is currently mired in an affordable housing crisis. And the situation seemingly grows more dire by the day. As Gothamist reported earlier this year, weakened rent laws and economic pressures have made the problem worse (In its recent report, the Coalition for the Homeless said that in February 2019, “an average of 63,615 men, women, and children slept in New York City shelters each night, just shy of the all-time record set in January”). Although earlier this year Mayor Bill de Blasio touted that the city has financed a record total 34,160 affordable homes in 2018, critics have said that a very small percentage of those homes was actually allocated to the poorest New Yorkers.

On the development side, one example of how the city is trying to combat the housing shortage is something called Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH). The Department of City Planning and the Department of Housing and Development formulated this zoning tool that requires developers to incorporate affordable housing into new development projects in rezoned areas. In 2016, the City Council revised the MIH policy. As stated on the City's Council website, the goals of the MIH modification were to “reach lower income households while maintaining flexibility; close loopholes in the program administration; improve transparency; address safety and local hiring concerns; and address problems of displacement and tenant harassment.”

But the question remains whether Mandatory Inclusionary Housing is actually an effective way to provide more affordable housing overall, or is it just a patch on a fundamentally broken system. There may be no clear-cut answer to that complicated question -- but first we'll look at the issues and consequences surrounding the crisis.

Who's Affected?

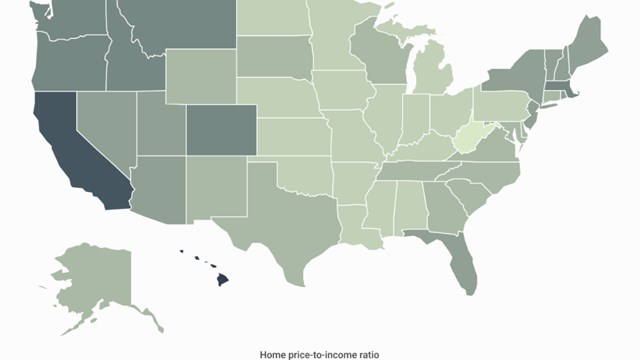

In today’s New York, land is becoming increasingly scarce as the number of vacant parcels continues to dwindle. As Jason Barr, professor of economics at Rutgers University-Newark, explains in his blog Skynomics, a square foot of land in East Hampton, Connecticut cost $184; a square foot in Brooklyn costs $667, and in Manhattan the price jumps to over $1,000. It's simple supply and demand: when supply is limited, prices climb. That is one of the main reasons housing is so expensive in New York City, and it is expected to get worse.

So when new development does happen, where does it get built? For the most part, it takes place in the more fringe areas of the city, such as sites along the Grand Concourse in the Bronx; Upper Manhattan; and the Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn. To be sure, these areas aren't uninhabited wastelands; these are neighborhoods that often have deeply rooted and established communities of working-class and immigrant New Yorkers. These communities are often faced with substantial change when new housing development arrives, which is why the City Council adopted a more responsive approach.

The Gentrification Factor

Gentrification continues to be a polarizing issue in the Big Apple as well in other major American cities. In recent years, the result of gentrification in neighborhoods at the lower rung of the economic ladder has been the displacement of longtime residents; the economic pressure of wealthier newcomers willing to absorb the higher rents and purchase prices offered for new or rehabilitated housing often forces longtime residents and small business owners out -- regardless of how long they and their families have called the area home.

Barr points out that New York City’s poorer neighborhoods have always been areas in flux, functioning as something of an incubator for immigrant groups as they arrived in America and began to climb the economic ladder. Using Manhattan's Lower East Side as an example, Barr cites how since the 1850s, the neighborhood has been home to successive waves of residents: German, Irish, Italian, Jewish, Puerto Rican, African American, and Asian communities have dominated the area's demographic in successive -- and often overlapping -- waves. According to Barr, the academic term for this phenomenon is 'ethnic ascension.'

What is different today is that the new arrivals on the Lower East Side are more likely to be wealthy young transplants who are able -- either on their own, or with financial assistance from their families -- to purchase expensive new luxury condominiums in glass towers rising above the old tenements. Even the neighborhood's historic buildings aren’t necessarily home to the poor any longer. Many have been renovated to house newly-minted college grads seeking to start a life in the big city. And what happens to those who can’t afford to stay any longer? Often, they are forced to move farther out, severing ties with family, neighbors and blocks they have known all their lives. That’s displacement, and the uprooting and sudden disruption that goes with it is what separates displacement from ethnic ascension.

Is MIH Effective?

As stated earlier, the City Council amended MIH back in March 2016. The modification called for 20 percent of certain developments—specifically, new construction in upzoned areas—to be set aside for residents making 40 percent of the area’s average median income. It also increased “the share of residential stories required to contain affordable units when provided in the same building as market-rate units,” from 50 to 65 percent.

But MIH has received its share of criticism, claiming that “The percentage and income level of the affordable units will fail to create sufficient units for the most low-income families.” Some have even labeled MIH itself as “an agent for gentrification,” arguing that the zoning tool doesn’t go far enough.

Matthew Lasner, an associate professor in the Urban Policy and Planning department at Hunter College, suggests that people need to be realistic when setting goals. “Short of the kind of ‘blue-sky’ proposals that I would advocate for -- which would include a kind of universal Section 8 voucher type program, and much more funding for subsidized public housing -- we have to find ways to expand the current public/private system of public housing.”

One idea, Lasner says, is to get rid of MIH in upzoned areas only, "and make it truly mandatory everywhere.” In simple terms, he advocates that to make MIH work it needs to be applied universally -- not just to neighborhoods in flux.

Barr predicts that one likely result of a broader, more pervasive MIH program will be pushback from residents who object to lower-income housing in their neighborhood. This NIMBY ('Not In My Backyard') attitude has plagued the development of fair housing policy long before gentrification and displacement were pressing concerns in so many parts of the city. And it's not just low-income housing that people object to; every time the city plans to place a homeless shelter in an upscale neighborhood, it is usually is met by opposition as well.

To Rent or to Buy?

Another consideration in the development of affordable housing is whether it should be built as a rental property or owned property. The answer is probably both. Lasner says “Ownership is a good thing in moderation. Ownership works really well for a lot of the middle class and some of the working class -- but ownership can also prove a burden.”

It can also lead to other problems. “Mitchell-Lama was a fantastic program,” says Lasner, speaking about the city-subsidized cooperative program that converted hundreds of struggling rental buildings to resident-run co-ops in the 1980s. “But there were concerns about racial implications, as it was a program that was viewed as a way to stop so-called ‘white-flight.’ That has changed today. Mitchell-Lama could look a lot different today, more like Co-op City, which is majority people of color.”

In our next installment, we’ll look at Mitchell-Lama, the Upper West Side Renewal District, and the possibility of a Mitchell-Lama version 2.0.

AJ Sidransky is a staff writer at The Cooperator, and a published novelist.

Leave a Comment